Wot I Think: Kine

Top of the blocks

Kine! What a wonderfully opaque, wide-ranging word. It apparently means “cattle” or “excellent” in Hawaiian Pidgin English, but I'm guessing the nod here is to “kinematics” as in “abstract, mechanical motion”. That explains about half of Gwen Frey's swish, challenging puzzler -- her solo debut, after leaving Flame in the Flood developer The Molasses Flood and founding new studio Chump Squad. At its most elementary, it's a game about rolling blocks around small, densely furnished grids towards an exit square. But it's also, somehow, about jazz, blues, friendship, romance and hitting the Big Time, set in a glorious Hollywood twilight of purple and brass. Here's Wot I Think.

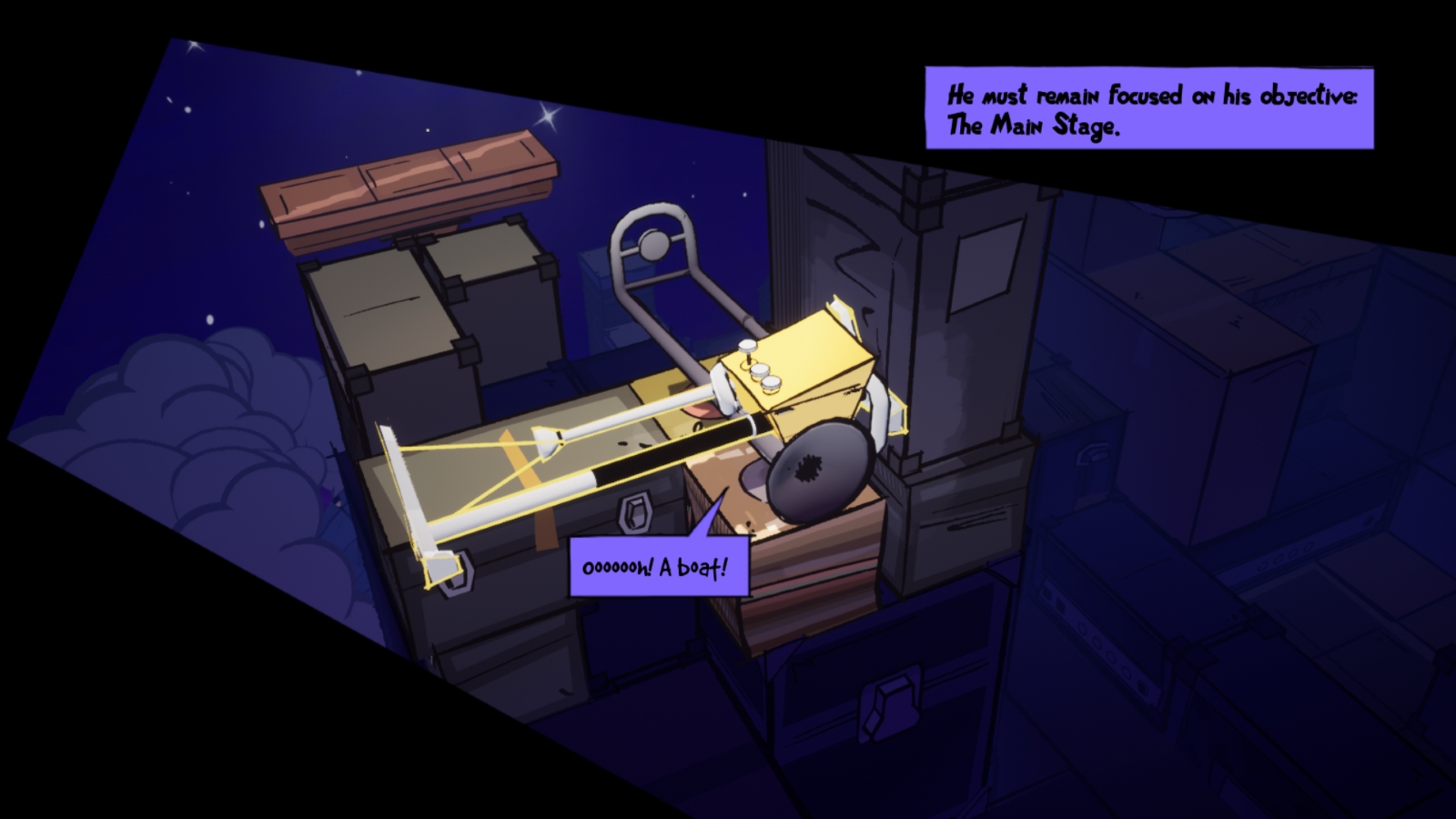

Those blocks? They are up-and-coming musicians with jaunty little faces, who jiggle along to the soundtrack when left to their own devices. They also happen to be musical instruments -- a drum, an accordion and a trombone -- whose moving parts can be either tools or hindrances. The puzzles they negotiate are steps on the way to a spotlit Main Stage at the top of the world map, where fame, fortune and (in my case) horrible migraines await. It's like La La Land, if La La Land was three interlocking Rubik's cubes. It's by turns good fun and rather exhausting.

The first difficulty is getting your head around those instruments and their appendages. These can be used to shunt the character around - standing them up vertically, for instance, so that you can topple the character across a gap. But they also hem you in, with levels annoyingly full of pillars, crevices and jutting overhangs to get in the way.

Quat the drum is the easiest to manoeuvre, with a cymbal that slides back and forth, allowing him to kick off walls and push himself through holes without rolling. Roo, the accordion, is tougher. You can pull out her bellows, allowing her to roll forward or sideways, or pop out the stands to either side, allowing her to roll backward or forward. Euler, the trombone, is trickiest of all: his horn and tube form an awkward reversible L-shape. Each character can serve as a platform for the others, and only one of them needs to reach the exit to complete the level.

I've developed a terrible headache just trying to describe all this in a way that won't prompt visions of Cthulhu ascending from the cosmic abyss with its complexity. Fortunately, Kine is quite good at instilling its basics and helping them mesh together in your puny human brain, not least because the evolution of the puzzles coincides with the unfolding of the story. The characters begin alone, allowing you to master them as individuals, but eventually fall in together on their quest for stardom, unlocking sets of puzzles with two or three participants.

Each puzzle sequence is also offered structure and charisma by a smooth-sipping blues and jazz soundtrack, which layers up for every conun-drum beaten and every obstacle trump(et)ed. It creates a sense of momentum akin to one of those big Broadway street scenes, where the lead singer starts off alone and gradually ropes every last onlooker into the routine.

Kine can be very artful about how it turns the sober business of spatial reasoning into a vehicle for personality, whimsy, and even courtship. In one series of puzzles you'll take Roo and Euler on a date, spinning them around and lifting one character with the other in a deranged but cute approximation of disco dancing. Less charmingly, you'll help Quat and Roo sell their artistic souls to an advertising company, rolling them amongst piles of paperwork while they grumble about the gig economy.

There are snappily worded comic book speech bubbles to set the scene (and toss you the odd clue), but much of the tale is conveyed by the game's shape-shifting environment, a backstage limbo piled high with props that can be rearranged to suggest an office, a jazz club or a Tunnel of Love. It's a beautiful creation, lit by flashbulb stars and fringed by gouts of dry ice. Spin the view, and parts of the scenery lift out of the way like theatre facades.

But even though Kine does a great job of drip-feeding you its complexities, I hit a wall once I reached the main stage. From this point, you have to wrangle with all three performers together, chaining together the shapes they form and dealing with their tendency to get in each other's way. You might have to, say, transport Euler from a lonely precipice to the exit by stacking and restacking Roo and Quat to create a series of platforms. These middle levels can be more of a chore than a delight if block puzzles in general aren't your jam. There's a real rush of achievement when you nail the sequence, but there are dead ends aplenty - and the more frustrated you get, the more pressing Kine's handful of blemishes become.

The game's visual language could use a slight rejig, for one thing. The cast are loveable creatures, but as 3D puzzle pieces I find them tiring to read: there's just a bit too much going on for comfort. The keyboard controls are slightly fussy, too. You can reset individual moves or the entire puzzle at will, which is certainly handy, but there's also a bug at the time of writing where the input for changing a character's shape gets stuck on “reset” till you click the board. I also chafed against the game's 90 degree camera angles when tackling some layouts – you can angle the view freely by holding right-click, but it reverts to those fixed perspectives when you let go.

Perhaps most seriously of all, getting stuck turns that otherwise euphoric, looping soundtrack into a grind. If this is a Broadway street scene, it's one in which the star keeps losing their bearings, pirouetting aimlessly between a lamppost and a hotdog stand while the orchestra churns through the same four-to-eight bars, again and again. Sometimes you can't even beat the first puzzle, trapping the score at the opening percussion layer, and start to feel less like Gene Kelly and more like creepy Toby Maguire in Spider-Man 3. There's a curious discordance between the music and the musical instruments in your charge, who sound off when selected or moved. This helps you distinguish them, but also means there's a constant, deadening barrage of stray notes or drumbeats even when you know what you're doing.

I'm not sure there's grounds for it, but I want to read more into that discordance. Kine might organise itself like a musical composition, but it also keeps you at arm's length from the music. You're here to move the performers around, not strut your stuff. Perhaps the moral of the story there is that raw talent only gets you so far; that the biggest stars took off not just because they had the best tunes, but because they had managers who knew how to move them up the ladder. Or perhaps this is just a game that, for all its enormous cleverness and warmth, hasn't quite put the pieces together.